It’s not wrong to say that at some level every Australian is worried. Since the economic disasters that have been Covid, Climate Change and the Ukraine War prices for everything have gone up. Nowhere has this been more notable in the price of food which has gone up significantly in the last few months alone. Prices are going up, serving sizes are getting smaller, and restaurants and other businesses are closing down, it’s no wonder people are asking whether Australia is vulnerable to food shortages.

Why have prices for everything gone up?

This is an unfortunate discussion because there’s no polite answer to it. The short answer is that large corporations have decided to do so in order to protect themselves. There’s a lot of nuance to that, but as much as we can blame the natural crises and war for starting the chain of events, the reality is that the current crisis has been caused by a combination of greed and a weak economic framework.

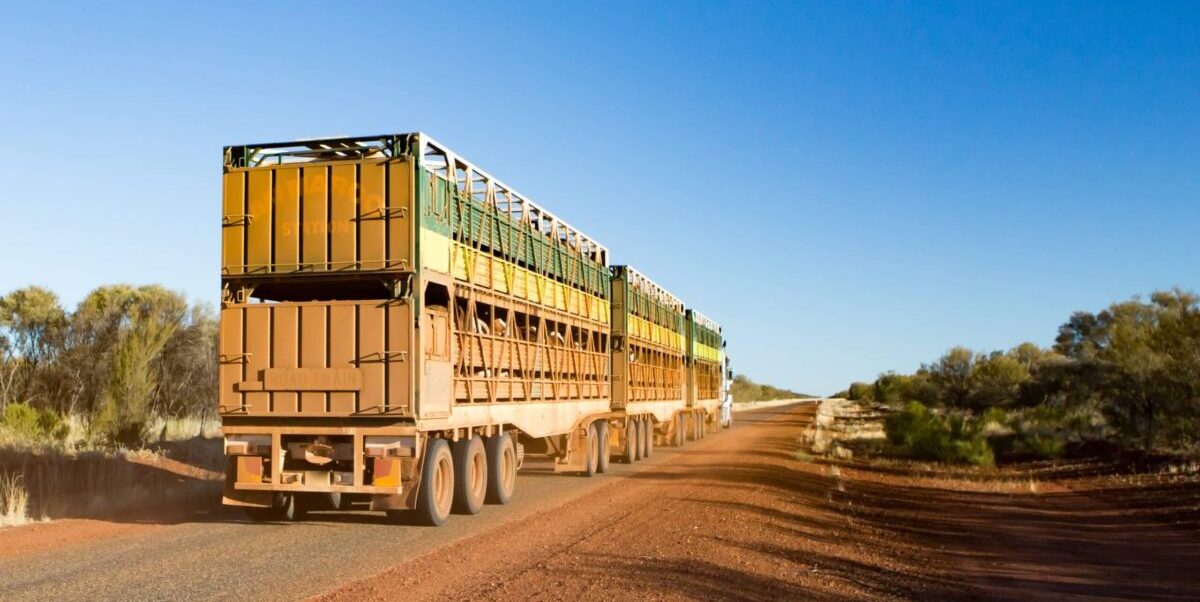

To begin with, let’s start with the concept of Supply and Demand. This is the economic theory that prices are dictated by the relationship between how much of an item is in supply, and how much people want it – in other words how much people are willing or able to pay for it. Let’s start by looking at supply. Covid, Climate Change and Ukraine all affected the supply of goods. In the case of Covid, the reason is obvious: many places simply shut down and many never reopened. During Covid, the global supply chain was severely disrupted and in many areas – particularly the trucking industry – that has led to waiting times getting longer as fewer drivers are available to transport an increasing demand for goods.

Transport and Trucking Crisis

A more in-depth discussion on the trucking crisis from a trucker’s perspective can be found here, but here’s the shorthand. Drivers are paid for mileage, not for wait time. The more time they spend waiting the less they get paid. It’s already low pay. It’s a dangerous job. It’s highly isolating. Many warehouses and logistic corporations don’t really care – they get paid for storing items so they don’t need to transport anything to get paid, everything being slower actually profits them, only adding a stark contrast to the way people are valued. The supply is there, the demand exists, but the corporations in between are able to profit regardless of whether the demand is met, with workers they don’t need to pay if the demand isn’t met, and this brings us to our earlier point – large corporations have created the trucking crisis. We see this sort of situation playing out again and again in other areas where workers are underpaid, unpaid or even punished for time spent on the job. It’s worth noting, Covid may have started this chain of events, but it’s not the only reason for the crisis or why it’s been sustained for so long.

Chocolate, Cattle and Climate Change

Next up is climate change. The fact is that many of our favourite products are becoming rarer. The global chocolate shortage has nothing to do with greedy corporate practices (although there are many unethical labour practices like child and slave labour in that industry) and everything to do with the fact that the world is simply becoming less able to support the cacao bean in general. Although we haven’t seen the full effects of this yet, naturally that means prices will rise in order to compensate for the lower supply bringing in less profit. In a few years, chocolate – real chocolate – will soon be a luxury good, but we should remember that artificial alternatives are an option. In fact, many companies in a push to move away from unethical practices already use artificial chocolate flavouring, and for many other products affected by climate change, this is an option too. With artificial competition prices for the commodity are forced to stay low.

We’ll be coming back to this point later but for now, the supply of real chocolate is going down which will drive prices up, but with artificial substitutes readily available, there will still be relatively affordable options. And you might be surprised to learn that this logic applies even to the meat industry. Australian Cattle Prices are going up, thanks in part to climate change and in part to abusive business practices like floodplain harvesting, with meat, in general, becoming much more expensive.

With that said, partly thanks to the push for ethical food practices from veganism, artificial meat grown in a lab is becoming a thing. Is it the same? Will there still be people who prefer natural beef over artificial? Absolutely, and until artificial alternatives are accepted by consumers and available for mass production, prices will go up and stay up.

Ukraine War Sanctions and Exploitation

Finally, Ukraine. Thanks to the war Ukraine is famous as an exporter of food and oil, and the recent war has sent the supply chain into shock. Not only has the supply dropped thanks to Ukraine’s food being inaccessible, but other countries have been lost as well. Russia was also a major exporter of food, but with the global sanctions levied against them, many countries have stopped trading with Russia – meaning two major exporters of food have been taken off the market. Similar trade embargos can be found on other products in other areas as well, resulting in supply being severely cut down and cut back.

But this is to be expected right? I mean, Russia has been a known aggressor for many years now – the Russo-Ukraine war began in 2014 after all, the invasion only began in 2022, and sanctions like this have been used many times in the past. So why is it hitting us so hard?

For a long time, most supermarkets and even most companies around the world have been engaging in the “just in time” business model. It’s the idea that products shouldn’t be kept in reserve on-site, but rather only what is likely to be bought on that day should be supplied to stores, with only small incremental changes based on demand. This is why shelves are empty, it’s not because the food or other items don’t exist, it’s just because the entire system is only intended to match the predicted demand of the day.

Now, for the most part, this isn’t a bad business model – but many companies apply this to their entire business model. We produce far more food than we need, but why pay for storage if most of it is going to go to waste anyway? Might as well throw out the surplus (and not pay the farmers for the excess) long before it reaches the warehouse because you don’t need to oversupply, you only need “just enough” delivered “just in time”. And it doesn’t hurt that this is what consumers want anyway.

Many consumers will look for food items that have a far-off expiry date, and if the expiry date gets close the food is going to get thrown out. Why pay for all that transport and storage only to put it on the shelf and have it go to waste? It’s much more economically efficient to only buy enough to meet the demand, and if farmers get screwed in the process because their oversupply of goods aren’t being bought, that isn’t the corporation’s problem (there are of course many other ways farmers get screwed over by this process as well but that is a much longer debate).

The problem is this practice only works when business is stable and predictable. If people rush the stores seeking to buy produce in bulk in order to protect themselves from a coming price hike, then the stores run dry very quickly. Now the corporations don’t mind, they can just resupply at their own pace and raise the prices for the next day just as planned, but for everyone else? The consumers? Well not only do we suffer because the price has gone up but we also suffer when the shelves are physically empty. Not only that but when it’s “well known” that there’s going to be a price hike, many corporations realise they can simply raise their prices even if they’re unaffected by global issues.

After the Ukraine war began, and everyone “knew” that oil prices would increase, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Exxon and Shell all reported record profits in 2022. Why? Because they raised the prices far higher than the supply drop actually required. Simply put, they exploited the fact that we all knew a price hike was coming in order to raise prices even further. Just to use one example, in this time of “crisis”, the largest company, Shell, reported a $40 billion dollar profit, double the profits of the previous year and more than they’ve ever made in the past 115 years. Just like profiting from warehousing during the transport and trucking crisis, companies and corporations have found ways to profit regardless of the supposed system of supply and demand.

So Answer the Question, Is Australia Vulnerable to Food Shortages?

In short? Yes, but it has much more to do with our practices as consumers and corporate practices of business than any simple question of “supply” or “crisis”. If we, as consumers, develop a liking for product substitutes – like lab-grown meat or faux chocolate, or become more willing to buy products close to expiry – then our actions as consumers should help stabilise any issue that comes out of supply. But if large corporations continue to find ways to profit while ignoring supply and demand, utilise exploitative practices to manipulate demand, or withhold products from the shelves in order to increase the impact of the crisis and provide themselves with a healthy buffer, then prices are going to rise and shortages are going to happen regardless of what supply, demand or the actual crisis might otherwise imply.

Solutions for this problem are few and far between, and it’s often hard to agree on answers. Is more regulation required? Should large monopolistic corporations be subdivided and forcibly separated out? Should businesses be forced to spend more on storage? Should we stop globalisation and international trade practices in order to focus on self-reliance, or should we increase globalisation and diversify it? Should we rewrite our entire economic structure to focus on farmer-to-consumer business models rather than middle-man models, or should we promote small businesses as competition against larger corporations? Should we promote burgeoning international economies in the hopes of diversifying our supply of produce, or should we focus only on already established, more reliable options?

Many of these options are incompatible with one another, and border on many different economic and social worldviews. What the evidence shows, however, is that many of these issues are primarily the product of existing corporate practices – not the product of the existing crises – many of which are abusive and exploitative, but the corporations would argue that these practices are why produce was so cheap, to begin with. However, at the end of the day, if Australia does suffer food shortages, it won’t be the crisis that is to blame.